redcardroy

ETL-AP

- Joined

- May 22, 2014

- Messages

- 225

I was explained this by someone who specializes in retail loss prevention. I think it's a good way to show AP and non-AP tm's how important it is to work together to reduce shrink.

TLDR: For every dollar of shrink, it takes about $34 of revenue (sales) to make up for the loss on Target's books.

Here's why:

Every public company has an income statement that describes what happens to every dollar of revenue (sales) that comes into the company.

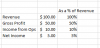

Here's a very simple condensed income statement...

In this ^ example, the company generated $100 in revenue. Of that, the company's immediate cost to purchase the merchandise was $50, so the gross profit (revenue - cost of goods sold) is the other $50. Once you subtract the operating expenses (administration, rent, utilities, upkeep, etc.), you're left with $10 (known as "income from operations"). Then after you subtract for non-operating expenses such as interest/amortization expenses, you're left with a grand total of $5. That means for every dollar that you generated in revenue, you only made 5% of it by the time all your expenses were paid. This would mean that if you lose cash or something with the cash equivalent of $100, you would need to generate 20x (100/5) that loss in the form of revenue to make up for the $100 loss in net income. So that means you need to make $2,000 in revenue just to make up for the $100 loss in net income. And that's assuming all your net income is cash (whereas in the real world, it's often credit, credit that you haven't collected yet). Now realistically, a 5% net profit margin is a little too generous for a retail company. Target's net profit margin over the last 6 years is more like 2.9%. That would give us a multiple of 34.48 (100/2.9) instead of 20.

TLDR: For every dollar of shrink, it takes about $34 of revenue (sales) to make up for the loss on Target's books.

Here's why:

Every public company has an income statement that describes what happens to every dollar of revenue (sales) that comes into the company.

Here's a very simple condensed income statement...

In this ^ example, the company generated $100 in revenue. Of that, the company's immediate cost to purchase the merchandise was $50, so the gross profit (revenue - cost of goods sold) is the other $50. Once you subtract the operating expenses (administration, rent, utilities, upkeep, etc.), you're left with $10 (known as "income from operations"). Then after you subtract for non-operating expenses such as interest/amortization expenses, you're left with a grand total of $5. That means for every dollar that you generated in revenue, you only made 5% of it by the time all your expenses were paid. This would mean that if you lose cash or something with the cash equivalent of $100, you would need to generate 20x (100/5) that loss in the form of revenue to make up for the $100 loss in net income. So that means you need to make $2,000 in revenue just to make up for the $100 loss in net income. And that's assuming all your net income is cash (whereas in the real world, it's often credit, credit that you haven't collected yet). Now realistically, a 5% net profit margin is a little too generous for a retail company. Target's net profit margin over the last 6 years is more like 2.9%. That would give us a multiple of 34.48 (100/2.9) instead of 20.